Deep okayness as a subjective choice of beliefs

What separates people who are content from those who aren’t?

Tl; dr: glass half full.

Ok, it’s a myriad of nonlinear causal factors and luck, but I propose one factor that might be particularly important: They have a different set of unfalsifiable beliefs about the world that make them deeply okay with whatever happens to them. This makes them more likely to experiment, try new things, or meet new people, and hence they get more tries to find what they enjoy than most people.1 Plus, even when they fail, they aren’t too disheartened because they’re willing to try again.

Beliefs that are actually real and lead to falsifiable predictions:

- I can drive to Berkeley in 40 minutes (answer: no)

- I know or don’t know X skill right now.

Beliefs that are maybe falsifiable, but in practice depend mostly on yourself and how hard you try,2 or on deep motives of others that are effectively impossible to falsify:

- Most people I’m interacting with at this dinner are just here for soulless networking and not to actually make friends.

- If I join this event, people will feel slightly uncomfortable because I’ve never been here before.

- When I try something new, I’m more likely to fail than [someone else who seems naturally talented at learning something new].

- I probably can’t learn X skill in 3 months.

Now, consider a different set of beliefs:

- People here are super memey and, despite being naturally good at networking, are also very friendly.

- The people at this event are excited when new people join because they like to see newbies learn their activity.

- I’ve successfully learned new skills before, so this time is no different.

Both of these sets of beliefs can mostly explain anything. E.g. if someone is rude to you at the event, it’s (a) a sign of greater enmity from others; or (b) that guy was just a jerk and everyone else is nice. Also, in many of these beliefs your actions affect whether or not they’ll be true. If you believe you can learn a skill in 3 months, you’re much more likely to do so than someone who doesn’t, because you’ll try harder. It’s reverse causality at work. Thus, it’s hard to say either set of beliefs is better, because they’ll probably be mostly right if you believe each of them.

The most obvious example is “Today was a bad day.” It only is if you believe it is, because you might instead believe that there’s something to be learned from any experience, “good” or “bad.”

Since neither set of beliefs has a better track record, maybe it’s better to just believe the world is nice.3

A scattering of other good thoughts

- Half-assing it with everything you’ve got

- How I Attained Persistent Self-Love, or, I Demand Deep Okayness For Everyone

Notes

-

More darts to throw at the board of person-environment fit, one might say. ↩

-

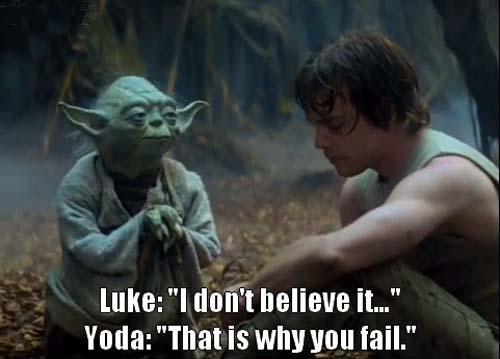

Aka, embedded agency (Yoda Do or Do Not). ↩

-

Caveat:

I have no idea how to do thisFiguring out how to do this is outside the scope of this post. As always, if the problem seems simple, it’s probably very hard to fix. ↩