Unintuitive conclusions from urban planning

Cars are weird. Living in a Massachusetts suburb, I didn’t realize just how car-dependent my area was1 until spending time in the SF Bay Area, which (while certainly not the pinnacle of transit) offers far more accessible bike and transit options.

This realization has made me quite sad about the current state of affairs, and because of this, I’ve recently fallen into a rabbithole of reading about transit. Here are some rather unintuitive facts about traffic, transit, and urban planning:

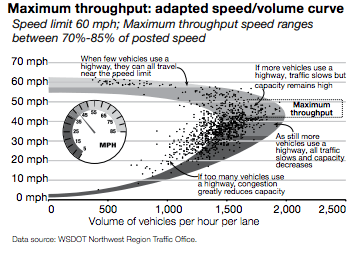

Highways exhibit highly nonlinear congestion

Figure provided by WSDOT 2018, from Strong Towns.

Let’s suppose you’re trying to maximize the vehicles-per-hour on a highway. As it turns out, adding more cars only improves this until a threshold, at which point it causes capacity to plummet. This phenomenon is shown in the graph above: as you add more cars, you descend the curve. At the middle, you have the maximum vehicles-per-hour. But as you keep going, the average speed of each car drops due to congestion, so even though more cars are on the highway at any one time, the total number of cars passing through declines precipitously.

This effect is so large that in Portland’s I-5, the decline in driving from covid slightly reduced the entering traffic volume, which actually allowed more cars overall to use the highway.

This is part of why some states/countries have ramp metering and why congestion pricing for roads is a really good idea.

Expanding roads doesn’t improve traffic

This one is pretty well-known but bears repeating. Thanks to induced demand, adding more highway capacity causes more people to use the highway, because it’s now the most convenient option. Hence, the highway becomes more congested until it returns to the steady-state equilibrium of the maximum sadness people are okay with. This is usually when people start getting annoyed at congestion and push for the highway to be expanded.

There is one counterargument to this: even if congestion didn’t get any better, surely we at least were able to transport more people to places they wanted to go? I think the response to this is that while this is true, expanding roads also strengthens the norm that it’s ok to travel 10, or 20, or 30 miles for a brief errand. This alters the pattern of development such that people start building destinations further away. If we assume the quality of each destination is the same regardless of theoretical distance, this means we’re having people drive further, and experience equivalent levels of traffic, for the same quality of destination.

That seems bad.

The speed of public transit (may*) determine the speed of car transportation

This is the Downs-Thomson Paradox. Essentially, if cars were faster than public transit, then people would shift to using cars. Thus (assuming perfect substitutability), people would flock to cars until it becomes slower than transit. Public transit hence acts as a ceiling on car travel times.

This implies, similarly to induced demand, that expanding car infrastructure won’t improve car travel times. In fact, you might want to instead expand transit infrastructure – if you improve non-car transportation options, people will switch from cars to transit, making cars and transit faster.

However, is this paradox actually true in practice? It seems somewhat limited. Empirically, I can observe that it takes 22 minutes to drive from Acton to Lowell in Massachusetts, while transit takes 1 hour, 49 min. Granted, this is because of design issues on the commuter rail (routes only go into Boston, not radially to other towns), but take another example: Berkeley to Palo Alto. This takes 52 minutes by car and 1 hour, 34 min by train. (Ok, with congestion it takes 1-2 hours by car, which is maybe where the paradox comes in.)

It does seem to be a general trend, though, that cars are usually faster than transit in America. Probably, this is because our transit is so horrendous that the paradox doesn’t even apply because nobody uses transit anyway.

The upshot?

I don’t have any particularly strong conclusions for you, beyond that urban planning is complicated and very nonintuitive. However, it does seem like car-centric planning is usually bad, for transit and cars.

Also, I’m not an expert, so if you see anything horrendously wrong please do call it out. Good places to learn more are Strong Towns and the YouTube channel Not Just Bikes.

-

As in, the only road in and out from my house is a single-lane, 40 mph road with no bike route and no sidewalk. The train station (which only has trains every hour) is 5 miles away. Good luck not owning a car here. ↩