Why Have Exposure Notifications Failed?

Note: this post will provide a fairly US-centric view on exposure notifications and the surrounding sentiment. Much of what I say here isn’t likely to be true in other countries.

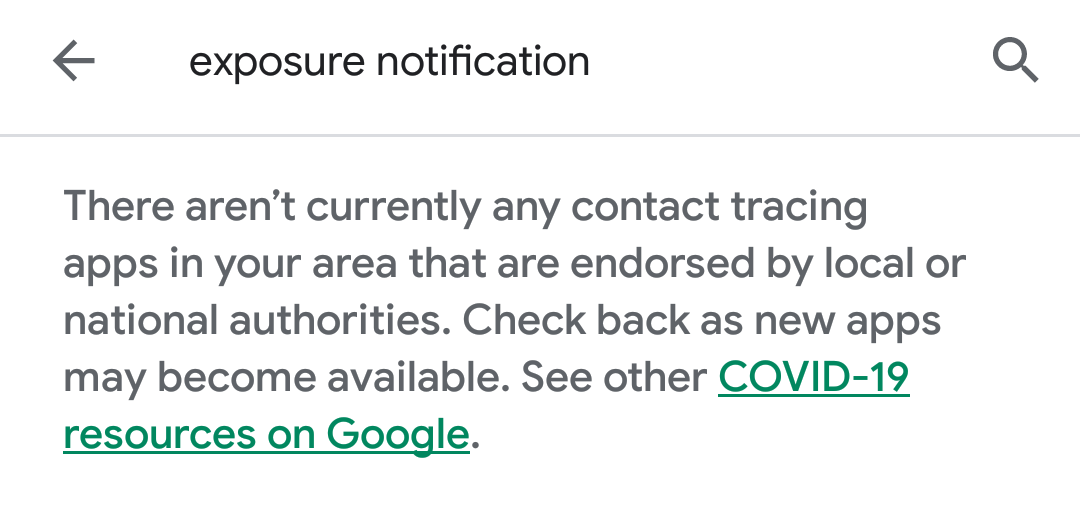

Exposure notifications, or contact tracing apps, have failed. It’s been months since I wrote my previous post on contact tracing, and yet here’s what I see when I try to download an app:

And I’m not alone.

Problem #1: No Apps Exist (in the US)

Thanks to the inaction of the federal government, there is no national policy for exposure notification. That leaves it up to the states, and according to 9to5Mac, just 4 of 50 states have said that they’ll use an exposure notification app.1 Essentially, most people in the US can’t get an app at all.

And because of privacy concerns, even though Apple and Google have already deployed Exposure Notifications tracing technology to billions of devices2, anyone who hasn’t installed an app and opted in will not have exposure notifications active, so they are effectively locked out of digital contact tracing. When you consider that for herd protection, scientists suggest that 60% of the population needs to opt in, this effectively makes digital contact tracing worthless in the US except in highly localized areas.

And even if an app is available…

Problem #2: Nobody Installs the App

The Eclectic Light Company blog tells it well. The highest uptake worldwide has been Iceland, at 40%3; in the US, numbers haven’t even gotten that high. North Dakota was the first to launch a contact tracing app, called Care19. However, as of June 11, less than 5% of the state had downloaded the app4. Why is this?

-

The app isn’t mandated. For example, India has made downloading their app mandatory to return to work and use public transit, netting it 100 million unique users since release4. China has used similar tactics to boost uptake of their apps as well.

Of course, a mandatory app may seem a little too totalitarian in the United States. (I argue that, if made open source and auditable, it wouldn’t be, but in any case it would be politically infeasible.) Instead, Harvard Business Review has suggested that we could boost voluntary uptake by using a similar strategy to Facebook and other social media apps: target specific and local communities first, such as families, schools, or other areas of gathering.3 The key point is to create targeted momentum and then scale out from there, rather than releasing broadly but indiscriminately.

-

The user experience of an app sucks. First, you have to know that there’s an app available in your region, which I suspect most people dont. Then, you have to find your specific app (often not distinguished in the store by your state) and download it. Many smartphone users have difficulties installing an app (low storage space, broken app store…), much less remembering to even go install it when they have little individual incentive. It would be better if Google & Apple could implement (completely private!) contact tracing and a UI for exposure notifications in the operating system, so that users wouldn’t have to download an app.5

Other Problems

- Some have said (e.g. the UK) that Bluetooth tracing is not very accurate. One improvement in this area is NOVID, an app that uses ultrasonic to obtain sub-meter accuracy. Unfortunately, the app isn’t open source and as of July 30 only has “10,000+” downloads on Google Play, so it again has little chance of taking off.

- People are mistrustful of contact tracing apps, despite Google & Apples’s protocol literally being designed to protect privacy at the expense of actually working. (See this Forbes article, which criticizes the protocol for shutting down innovation on contact tracing technologies.) Perhaps a well-aimed advertisement campaign could fix this, emphasizing the security and privacy guarantees that any contact tracing app would provide.

What Do We Do From Here?

It’s a tough problem, most of it being political rather than technological. (It reminds me of the well-known problem of coordination in technology.) On a personal level, obviously I’d recommend downloading the nearest app if available and telling all your friends to do so as well. Creating a local community of people equipped with contact tracing apps would be a good place to start.

On a national level, I’m obviously not very qualified to talk about concrete next steps, but generally, here’s what I think we need:

- Google & Apple should be more aggressive in pushing exposure notifications and enabling it even if the user doesn’t install an app. This should be supplemented with advertisements and news articles showing that it doesn’t infringe on personal privacy.

- The US needs a more coordinated tracing response. Considering our failing track record on almost every aspect of the pandemic, this one seems especially remote, but we need a unified system for both digital and perhaps physical contact tracing.

-

https://9to5mac.com/2020/07/13/covid-19-exposure-notification-api-states/ ↩

-

https://www.gsmarena.com/googles_efforts_in_making_android_updates_faster_have_paid_off_android_10_fastest_adopted_update-news-44198.php ↩

-

https://hbr.org/2020/07/how-to-get-people-to-actually-use-contact-tracing-apps ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.lawfareblog.com/what-ever-happened-digital-contact-tracing ↩ ↩2

-

To those of you worried about privacy concerns, I remind you that TikTok has been downloaded 175 milion times in the US. And TikTok is run by a Chinese company that is probably selling all your location data and sensitive information. If we can sacrifice total privacy for 7-second meme videos, maybe we can accept sharing a little (anonymous) data to save lives? ↩

If you like reading these posts, get new ones via email: